Diabetes Treatments: Evidence-Based Options and How They Work

Outline

Here is the roadmap we will follow:

– Why treatment matters: types of diabetes, goals, and risk reduction

– Lifestyle therapies: nutrition, activity, sleep, and stress as core treatments

– Oral medications: classes, mechanisms, pros, cons, and typical use-cases

– Injectable therapies: insulin strategies and incretin-based options

– Tools, procedures, and team-based care: technology, surgery, and personalized planning

– Conclusion: practical takeaways for moving forward with confidence

Why Treatment Matters: Types, Goals, and the Power of Early Action

Diabetes is not a single condition but a cluster of metabolic patterns that share elevated glucose as a common end-point. Type 1 involves autoimmune loss of insulin-producing beta cells and requires insulin from diagnosis. Type 2 combines insulin resistance with a relative shortfall in insulin over time; it often begins silently, sometimes years before detection. Gestational diabetes appears during pregnancy and demands prompt management to protect parent and baby. Prediabetes sits upstream and signals higher risk, but timely changes can alter the path ahead.

Clear goals help make sense of the options. For many non-pregnant adults, a common target for average glucose exposure is an A1C around 7%, though targets are individualized based on age, comorbidities, and risk of low glucose. Blood pressure control, lipid management, and smoking cessation are equally vital, because the cardiovascular system carries much of the burden in diabetes. Routine screening for eyes, kidneys, nerves, and feet enables earlier intervention.

Evidence shows that treating glucose effectively can lower complication risk. In people with type 1, intensive therapy reduced microvascular complications substantially in landmark research, with benefits echoing decades later. In type 2, each percentage point drop in A1C has been associated with a meaningful reduction in small‑vessel complications, and careful attention to blood pressure and cholesterol has reduced heart events and strokes. Importantly, the right target is the one that balances benefits with safety: fewer lows, fewer side effects, more days that feel livable.

Why act early? Because metabolic momentum builds. The longer glucose runs high, the more stress on eyes, kidneys, nerves, and vessels. Early lifestyle changes and appropriate medication can preserve beta-cell function longer and expand future options. That does not mean a race to perfection—rather, steady steps. Think of treatment as compound interest: gains made now tend to grow in value over time, especially when paired with routine monitoring and honest feedback loops between you and your care team.

Lifestyle Therapies That Treat the Root: Food, Movement, Sleep, and Stress

Lifestyle is not a side dish; it is core therapy and often the first lever to pull. Nutrition patterns that emphasize minimally processed foods, lean proteins, plant-based fats, and plenty of fiber can improve insulin sensitivity and flatten post-meal spikes. Many people do well with Mediterranean-style or plant-forward approaches, while others prefer lower-carbohydrate patterns. What matters most is an approach you can maintain, that nourishes you culturally and socially, and that produces measurable improvements in glucose and energy.

Key nutrition principles with solid evidence:

– Emphasize fiber: aiming for roughly 25–35 grams per day helps slow glucose absorption and supports satiety.

– Distribute protein across meals to stabilize appetite and preserve lean mass during weight loss.

– Choose carbohydrates with intact structure (whole grains, legumes, vegetables) to moderate post-meal rises.

– Consider portion-aware lower-carbohydrate options if post-meal spikes are hard to control.

Weight management is meaningful for many with type 2. Even a 5–10% weight reduction can improve A1C, blood pressure, and triglycerides. That does not require perfection or a single “right” diet. Calorie awareness, mindful eating, and structured meal timing—such as consistent eating windows that fit your schedule—can support progress, especially when paired with activity.

Physical activity acts like a systemic insulin sensitizer. A widely endorsed target is at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, spread over at least three days, plus two or more sessions of resistance training to build or maintain muscle. Short bouts matter: 10–15 minutes of light movement after meals can blunt glucose rises. On days when a full workout is unrealistic, consider movement “snacks”—a few minutes of brisk walking, stair climbing, or bodyweight exercises.

Sleep and stress round out the picture. Short or disrupted sleep and chronic stress hormones push glucose upward. Consistent bedtimes, light exposure in the morning, and wind‑down routines help. Simple breathing practices or brief guided relaxation can lower sympathetic drive and ease glucose volatility. The common thread: behavior change works best when it is specific, measurable, and kind. Swap “be perfect” for “iterate.” Track a couple of metrics—post‑meal readings, steps, or minutes of resistance work—and adjust weekly rather than waiting months for course corrections.

Oral Medications: How They Work, What They Change, and When to Use Them

Oral therapies expand the toolkit when lifestyle alone does not meet targets or when earlier pharmacologic support is appropriate. Different classes target distinct points in glucose regulation—liver output, intestinal absorption, renal handling, muscle uptake, and insulin secretion. Understanding these levers helps match therapy to goals, health history, and preferences.

Common classes and typical effects:

– Biguanides: Decrease hepatic glucose production and improve insulin sensitivity. They are often weight‑neutral or slightly weight‑reducing. Gastrointestinal upset can occur early; gradual dose titration and taking with meals help. Long-term use may lower vitamin B12 levels in some people, so periodic checks are sensible.

– Sulfonylureas and related secretagogues: Increase insulin release from the pancreas. They can reduce A1C efficiently but may cause hypoglycemia and weight gain; timing with meals and education about low-glucose signs are essential.

– Thiazolidinediones: Improve insulin sensitivity in adipose and muscle tissue. They tend to be weight‑neutral to weight‑gaining and can cause fluid retention; they are generally avoided in significant heart failure.

– Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: Promote urinary glucose excretion, modestly reduce weight and blood pressure, and have well-documented cardio-renal benefits in appropriate patients. Genital yeast infections and dehydration risk are possible; hydration and hygiene counseling mitigate issues.

– Dipeptidyl peptidase‑4 inhibitors: Enhance incretin signaling to increase meal‑stimulated insulin and suppress glucagon. They are weight‑neutral with low hypoglycemia risk but have modest A1C effects.

– Alpha‑glucosidase inhibitors: Slow carbohydrate digestion, blunting post‑meal spikes. Gastrointestinal gas and bloating can limit use; starting low and going slow helps.

In head-to-head terms, many oral agents lower A1C by roughly 0.5–1.5 percentage points, but the “fit” depends on comorbid needs: kidney and heart protection, weight goals, hypoglycemia tolerance, and cost. For example, if kidney disease or heart failure risks are priorities, agents with proven protection are often favored. If post-meal spikes dominate, targeting digestion or incretin pathways can be strategic. If a simple regimen is needed, once‑daily dosing may enhance adherence.

Practical tips for success:

– Start with a clear purpose: What problem is the drug solving—fasting highs, post‑meal highs, overall A1C, cardio‑renal risk?

– Simplify dosing and link it to daily anchors (breakfast, brushing teeth, evening routine).

– Watch for side effects in the first weeks; most are manageable with dose adjustments, timing, or supportive measures.

– Reassess at 8–12 weeks: If targets are unmet, consider add‑on therapy or a different class based on the data you’ve collected.

No single pill solves everything. Combined therapy—supported by nutrition, activity, and sleep—often produces steadier, more sustainable results, with fewer trade‑offs than escalating one agent alone.

Injectable Therapies: Insulin Strategies and Modern Incretin-Based Options

Injectables broaden the range of control when oral agents are insufficient or inappropriate. Insulin is essential in type 1 and often required in type 2 over time. The goal is to mimic physiologic patterns: a steady “basal” level to cover fasting needs, and “bolus” doses for meals. Basal insulin is typically started once daily and titrated every few days based on fasting readings. Mealtime insulin is matched to carbohydrate intake and pre‑meal glucose, often using a carbohydrate ratio and a correction factor.

Safety remains central. Hypoglycemia awareness training, understanding delayed lows after exercise, and carrying rapid carbohydrates matter. Rotating injection sites reduces lipodystrophy and preserves absorption. For people with shifting schedules, simplified regimens—such as adding basal insulin to existing oral therapy—can be a measured step before moving to full basal‑bolus plans.

Incretin-based injectables (glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists and related dual‑pathway agents) enhance meal‑time insulin, suppress glucagon, slow gastric emptying, and reduce appetite. Many users experience meaningful A1C reductions alongside weight loss, which can improve blood pressure, sleep apnea, and mobility. Gastrointestinal effects are common initially; slow titration and mindful meal pacing reduce discomfort. Cardiovascular outcome trials have shown benefits for certain agents in people with established risk—an important tie‑breaker when choosing among options.

Where do injectables fit?

– Type 1: Basal‑bolus therapy or pump therapy with rapid‑acting insulin is standard. Adjuncts may be considered selectively, but insulin remains foundational.

– Type 2: Consider injectables if A1C is markedly elevated, if symptoms of catabolism are present (weight loss, excessive thirst, frequent urination), or if oral combinations do not achieve goals. Incretin-based injectables are often used before insulin when weight and cardiovascular risk are prominent concerns.

Titration is a process, not a one‑time event. Data from home monitoring—fasting values, pre‑meal readings, and post‑meal checks—guide dose adjustments. When continuous glucose monitoring is available, time‑in‑range (typically 70–180 mg/dL for many adults) becomes a nuanced steering wheel, helping refine basal rates and mealtime strategies. Over time, the right mix of injectables can stabilize days and nights, reduce variability, and lessen the cognitive load of constant adjustments.

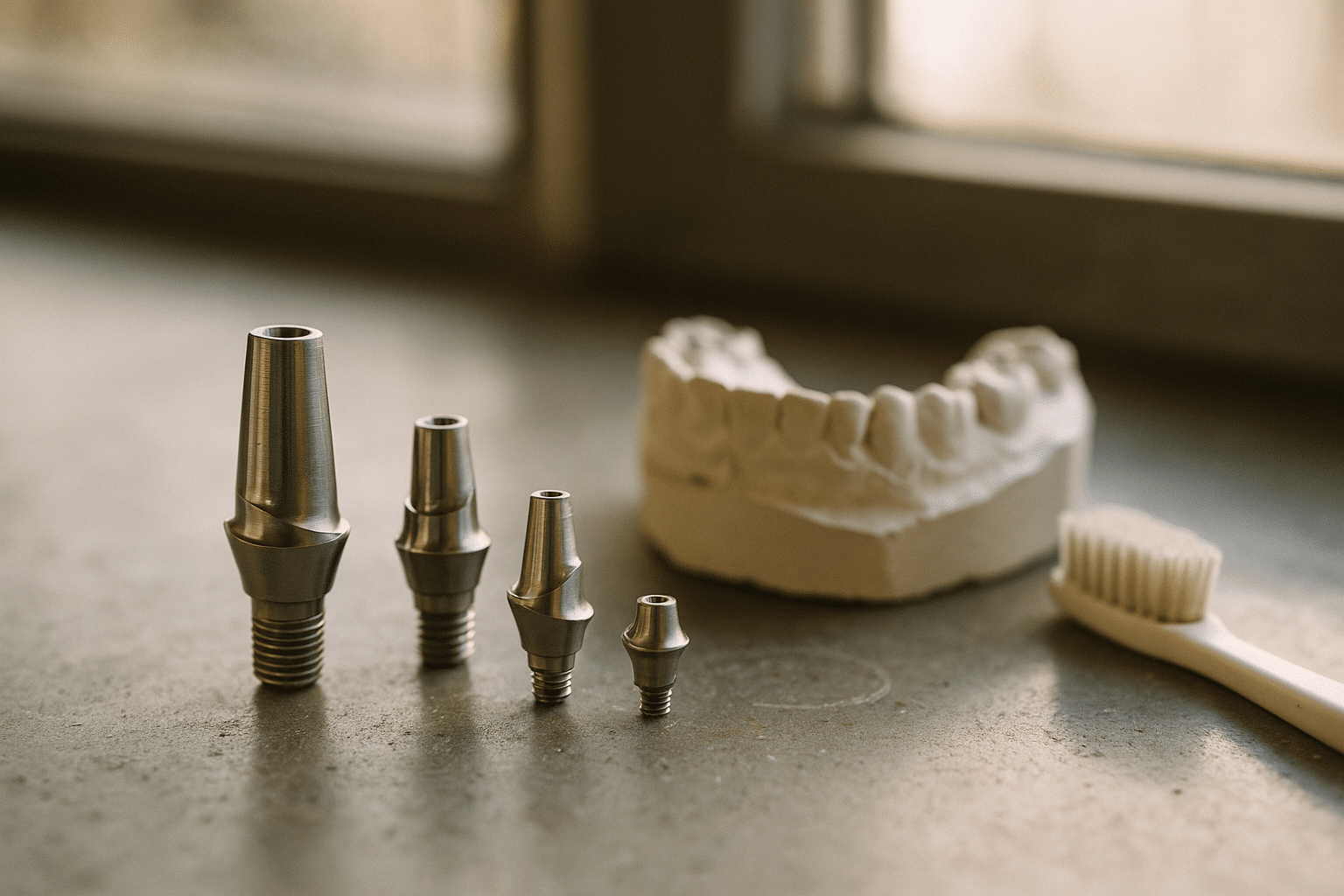

Tools, Procedures, and Team-Based Care: Technology, Surgery, and Personalization

Modern tools make daily decisions clearer. Continuous glucose monitoring provides near‑real‑time trends and alerts for highs and lows, turning sporadic snapshots into a moving picture. Time‑in‑range targets (often above 70% for many adults, individualized) correlate with reduced complications and better quality of life. Insulin pumps and smart pens can automate or track dosing, reduce missed mealtime doses, and capture data for pattern recognition. The value is not in gadgets for their own sake but in feedback that teaches what works on your schedule, meals, and training days.

Routine preventive care is as therapeutic as any drug:

– Annual dilated eye exams detect retinopathy while it is still reversible.

– Urine albumin checks and kidney function tests guide cardio‑renal protective therapy.

– Foot checks and comfortable, well‑fitting footwear prevent ulcers and infections.

– Vaccinations reduce infections that can destabilize glucose.

Metabolic (bariatric) surgery is a powerful option for some with type 2 and excess adiposity. Eligibility often includes body mass index criteria (commonly 40 or higher, or 35 or higher with inadequate control and comorbidities), with expanding consideration at lower ranges for selected patients. Surgery alters gut hormones and energy balance, frequently improving glucose homeostasis quickly. Many experience remission—commonly defined as sustained A1C under 6.5% for at least three months without glucose‑lowering medications. Long‑term success depends on nutrition, supplements, follow‑up, and readiness to embrace new routines.

Personalization is the thread connecting all of this. Culture, food preferences, work shifts, family duties, and financial constraints drive what is realistic. Some people prefer a small set of highly effective tools; others like detailed tracking. Either way, assembling a support team—primary clinician, diabetes educator, dietitian, pharmacist, behavioral health professional—makes the plan sturdier. Cost and access matter: choose treatments you can obtain consistently and build contingency plans for supply interruptions or travel. Finally, mental health support is not optional; anxiety, burnout, and depression can erode engagement and glucose control. Regular check‑ins about mood and motivation can be as impactful as dose adjustments.

Conclusion: Turning Options into a Plan You Can Live With

Diabetes treatment works best when it is practical, measurable, and yours. Start with clear goals, choose lifestyle changes that fit your life, and add medications that solve the specific problems your data reveal. Use technology if it reduces effort or worry, not because it is new. Reassess every few months, celebrate small wins, and adjust with intention. With a plan that respects your realities—and a team that listens—you can protect long‑term health while living the life you want today.